TO CAPTURE THE MODERN IMAGINATION?

ONLY IF IT SPREADS ITS COSMIC WINGS

Hilda Geraghty

(Published in The Furrow, an Irish pastoral monthly, February 2023)

Abstract: The Christian faith is in a crisis of the imagination. This is very serious because, as St. J.H. Newman says, “all beliefs- religious, secular and political-must first be credible to the imagination”. This article shows how our new understanding of the universe has unwittingly made the image of Christ smaller and paler in our imaginations, – what Teilhard de Chardin warned about. It shows the need for the Christian Church to give Christ his true place in the cosmos, as Teilhard reveals it to us.

In today’s Ireland we live in a culture where a child will probably grow to lose whatever Christian faith was imparted to it by older generations. Somehow the story of Jesus, and the whole biblical perspective around him, are no longer what they were for older generations: a picture of reality, a world view on which to build their lives. “It is now seen as archaic to hold Catholic values among the student body.” These are the words of one teacher who voiced concern during a survey on bullying in Irish schools. (1)

Archaic. The word stings. Of the past. Is this why it has got so hard to transmit faith per se as the future unfolds? If it has become archaic to many, the reason, to my mind, is that the Christian faith is in a crisis of the imagination. (Not, I hasten to add, an imaginary crisis, – it is all too real.)

By imagination I don’t mean fantasy, a power to conjure up what is unreal. I see it, rather, as the vital faculty that creates the images that lead to our dreams, and then drives us to pursue them. Could we ever climb a mountain, become a doctor, or take to the air, if we didn’t first imagine ourselves doing it? “Imagination is everything,” according to Einstein, “it is the preview of life’s coming attractions.” It is what makes things real to us, and we operate from there.

IMAGINATION AND THE FORMATION OF FAITH

However, it was St John Henry Newman who pointed out how critically important the imagination is to the formation of faith. Terrence Merrigan writes:

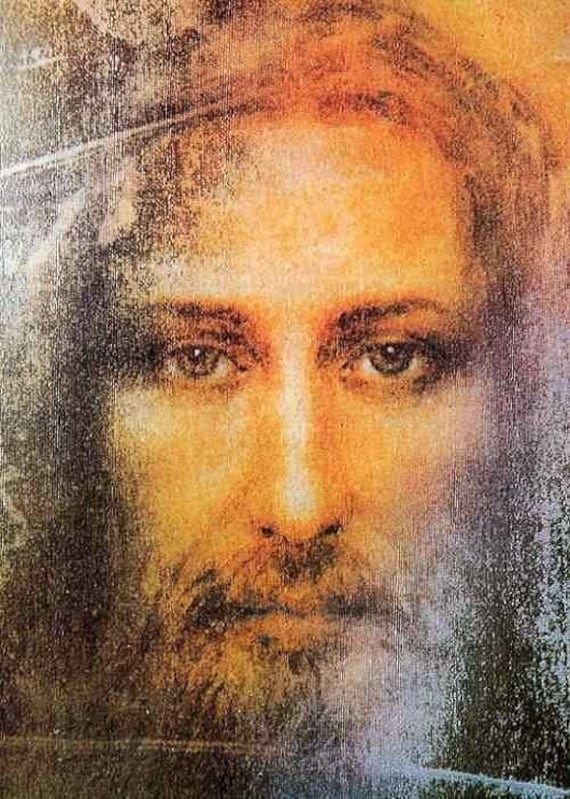

‘In the Grammar of Assent, Newman claims that “the original instrument” of conversion and the “principle of fellowship” among the first Christians was the “Thought or Image of Christ.” Moreover, this “central Image” continues to serve as the “vivifying idea both of the Christian body and of individuals in it.” The image of Christ is the principal of Christian fraternity, and the source and soul of Christian “moral life”. It “both creates faith, and then rewards it.” The whole life of the Church can be conceived as the endeavour to promote and perpetuate this image. Indeed, the whole life of the Church, its narrative tradition, its ethics, and its spirituality can be regarded as – ideally- the objectification of this image in history.’ [1]

What is the image of Christ that we as Church offer today? The low figures for religious practice, especially among the young, would suggest that this central, all-important image needs a whole new interpretation if the Church is to inspire people once again to follow Jesus.

Merrigan continues:

Newmans’s decision to explore religious faith in terms of the imagination was born of his conviction that “all beliefs- religious, secular and political- must first be credible to the imagination, the faculty which enables us to relate to an object as a ‘whole’ that is to say, as something with a claim on us.”

Indeed, for Newman, the entire religious history of humankind might be said to have its roots in an act of the imagination that shapes both our self-understanding, and our image of the Divine.

Newman went on to make the very interesting point: the Christian faith “appeals to the imagination, as a great fact, wherever it comes; it strikes the imagination.” Those who would do battle with it “must find some idea equally vivid…, something fascinating, something capable of possessing, engrossing and overwhelming; their cause is lost, unless they can do this.”’ [1]

But is this latter scenario, in reality, just what has happened to faith today? – An ‘equally vivid idea’ has taken hold of the modern imagination, not caused by any ‘who would do battle with it’ but rather by the startling increase in human scientific knowledge over the last three centuries. Teilhard de Chardin wondered, ‘Is the world not in the process of becoming more vast, more close, more dazzling…? Will it not burst our religion asunder? Eclipse our God?’

He was convinced that Christianity was now offering ‘too small a Christ’ to people living in the modern/postmodern world. This is a dangerous situation for the Church, because, as Leonard Sweet writes, ‘If something doesn’t capture the imagination, it doesn’t survive.’ 4

KNOCKED FOR SIX

The reality is that the Christian imagination has been suffering seismic shocks one after the other since the 17th century when modernity dawned. Until then the dramatic narrative of Genesis 1-3 at the opening of the Bible had gripped the western imagination with unparalleled power. It just explained so much! It revealed the nature of reality, the world as the creation of a good, unique, personal God; it gave the highest place in it to us humans, made in the image and likeness of God; it explained the problems of life as originating in our choosing self over God, with the ensuing loss of paradise and death. Then in the New Testament Jesus, Son of God, is presented as saving the human race from this fatal predicament it finds itself in.

For sixteen centuries the Genesis narrative functioned, to all intents and purposes, not only as a faith document but also as history and also as science. It was the only source of information about our remote past and origins, and people accepted it, given its credentials as Scripture, the revealed Word of God. We knew what life was all about, and western civilisation built itself on this foundation. And we were commissioned to spread this knowledge to the whole world.

The first seismic shock was when Copernicus and Galileo between them proved that the sun, moon and stars did not revolve around our planet, but the other way round. This news so dismayed the Church (and everyone else) that Galileo was forced to recant and put under house arrest until his death. Our self-importance as humans was dealt a blow: the sun, moon and stars didn’t all revolve around us!

Human knowledge had developed the scientific method. Modernity had taken its baby steps, soon to grow into gigantic leaps. Of these, the next seismic shock to the religious imagination was, of course, Darwin’s theory of evolution and natural selection. Was God the Creator needed any more, if life evolved and somehow created itself through continually adapting and perfecting itself?

While not condemning Darwin, the Church quietly disapproved, and many 19th and 20th century theologians rejected the notion of evolution (though interestingly Newman thought it made sense). The Church has since accepted it officially, as the Catechism of the Catholic Church affirms. While not naming evolution as such, it states that Creation ‘did not spring forth complete from the hands of the Creator. The universe was created ‘in a state of journeying’ (in statu viae) toward an ultimate perfection yet to be attained, to which God has destined it.’ 5 However, it does not go on to claim any cosmic role for Christ in this, but leaves the universe journey to God’s providence generally, as if it were a separate story from the salvation of human souls.

We can add in all that has happened since, as we explored the truly awesome macro and micro dimensions of the world, with ever more powerful instruments. So we now know that we live on a tiny planet in a universe of billions of galaxies, while beneath us the depths of matter descend to the quantum level. It may be scary, but it is definitely “fascinating, possessing, engrossing and overwhelming…“

HOW IS OUR FAITH TO COPE?

Who are we now? Do we matter in this vast universe? Or only to ourselves? And if we are believers, who is Christ now in this cosmic setting?

Since Teilhard’s time (d. 1955) the cosmos has loomed ever larger in our culture. To imaginations brought up on dinosaurs and Star Wars, to humans who have walked on the moon and now peer at the earliest universe, can we as Church offer a less-than-cosmic Christ? Not if the Christian faith is to make sense to minds and hearts today.

So, what is the role and function of Christ in this evolving cosmos? This is the urgent question that Teilhard de Chardin set himself to address throughout a lifetime of work, reflection and writing, because it was the key issue in his own personal life as a scientist and passionate Christian.

He lamented that in recent centuries the study of Christ, Christology, had not developed in tandem with human knowledge, hardly going beyond the definitions drawn up in the earliest centuries of the Church. “In a sense, Christ is in the Church in the same way as the sun is before our eyes. We see the same sun as our fathers saw, and yet we understand it in a much more magnificent way. I believe that the Church is still a child. Christ, by whom she lives, is immeasurably greater than she imagines. And yet, when thousands of years have gone by and Christ’s true face is a little more plainly seen, the Christians of those days will still, without any reservations, recite the Apostles’ Creed’. (7)

/462977main_sun_layers_full-5a83345e875db90037f173c3.jpg)

HAND IN GLOVE

It is a great pity that Vatican theologians were so resistant to Teilhard’s views that they forbade him to publish his writing at all. He was offering a totally renewed vision of what Christ’s incarnation means, by showing how it fits hand in glove with the magnificent universe story. The great purpose of the universe is to bring forth the fully evolved Christ as a single humanity, united to him in holiness, to the glory of God. “The whole future of the earth, as of religion, it seems to me, depends on awakening our faith in the future.”

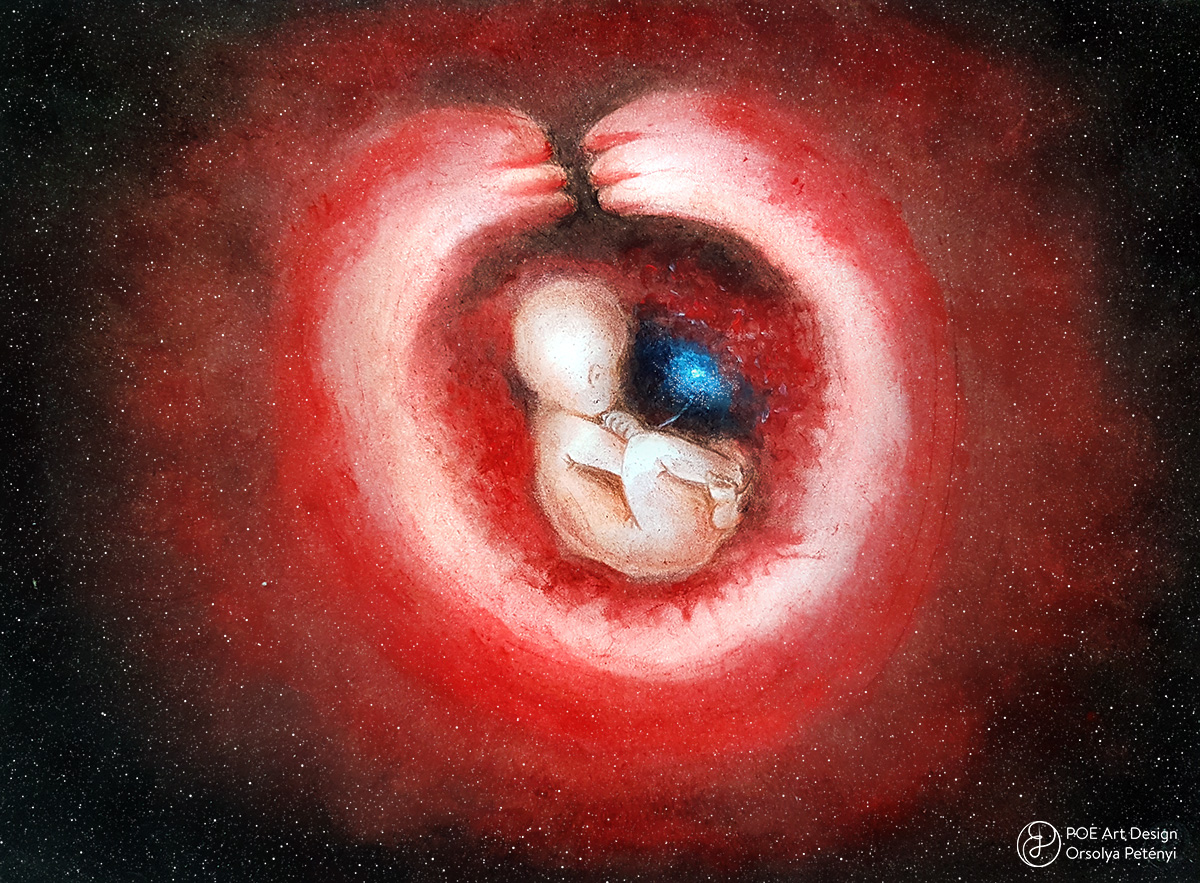

Christ is the One for whom the cosmos was made. Even more than a Saviour of humans, – though he is supremely that, the Divine Homo Sapiens is first and foremost the crowning glory and supreme work of God in this cosmos. By the fact of his physical birth into matter, Jesus is related to the earth, its total past, present and future, since everything is related to everything else in a seamless whole. Teilhard writes, ‘My irresistible tendency is to universalise what I love, because otherwise I cannot love it. Now, a Christ who extended to only a part of the Universe, a Christ who did not in some way assume the world in himself, would seem to me a Christ smaller than the Real… The God of our Faith would appear to me less grand, less dominant, than the Universe of our experience!” (12)

Christ is also the Omega point of evolution, glowing with the energy which, as the Divine Human, he has attained in rising out of death. A divine homo sapiens now sits on the throne of Heaven, living in a matter-spirit body without limitation. He remains among us as Love incarnate in Word and in Eucharist, the Divinised Matter of his real presence, to lead us to this destiny, forever uniting us to himself and to each other, generation after generation.

Our destiny is to evolve into the vast Christ, bringing the whole universe, which knows itself through us, to glorify God. ‘Go and teach all nations…’ Reality in its past, present and future is ALL for the Human God, in Teilhard’s unified vision.

THE POINT OF CONFLICT WITH THE CHURCH

While the Church has now accepted the reality of evolution, it would not allow Teilhard to reinterpret the doctrine of original sin in a cosmic setting, and it was this that led to his exile in China for the greater part of his life, forbidden to publish anything.

The Catechism, compiled in 1994 almost forty years after his death, still warns, ‘The Church, which has the mind of Christ, knows very well that we cannot tamper with the revelation of original sin without undermining the mystery of Christ.” (13)

That logic works both ways, Teilhard would say: if we develop a deeper, dynamic, cosmic understanding of Christ, Incarnation of God, we would need to correspondingly develop a deeper, cosmic and more credible understanding of sin and its origins. That issue, however, cannot be developed here.

EMPOWERING CHRISTIANS

To conclude, Teilhard unveils the cosmic dimensions of love, and of the Incarnation of God into matter. It is the worldview of a genius who unifies matter-spirit, body-soul, science-faith, Human-Divine, earth-heaven, into a single Whole. As such it has extraordinary power to attract and inspire the imagination. It reveals the cosmic wings of the Christian faith, and some people are happily flying, confident in a faith that is not afraid to come to terms with today’s culture. This could not be more important because, as Newman said, the imagination is where faith first forms in us. It makes faith real, and that is what galvanises us. The cosmic Christ gives us the sheer joy of living in a totally meaningful reality.

If made known by us as Church, and properly developed and taught, this worldview would empower and energise Christians for their task in the world, as Teilhard felt they needed to be. For him, it is an energy the Christian faith owes to the world, because Jesus the Christ came to transform it. To transform the world through a cosmic understanding of love, and to ‘save souls’, are actually two sides of one coin.

Teilhard’s genius is to uncover the oneness of all reality in Christ. By uniting matter and spirit, he reveals the full extent of the Incarnation. In this way he lights up the cosmic dimensions of the final words at the Last Supper, where Jesus points towards the future he longed for, and for which he gave his life:

“May they all be one.

Father, may they be one in us, as you are in me and I am in you,

so that the world may believe it was you who sent me.

(Jn 17:21)

Footnotes

1 The Furrow, December 2021, Difficult times for Catholic students in second Level Schools? The voices of RE teachers. p 698.

2 Essay by Terrence Merrigan, THE IMAGE OF THE WORD: FAITH AND IMAGINATION IN JOHN HENRY NEWMAN AND JOHN HICK, in JOHN NEWMAN AND THE WORD, edited by Terrence Merrigan & Ian.T. Ker. 2,000. LOUVAIN Theological and pastoral MONOGRAPHS 27, Peeters Press, Louvain. W.B.Werdmans, 2000. P.6

3 Quotations by Terrence Merrigan sourced on the internet which gave no reference, but are probably from Merrigan’s book The Imagination in the Life and Thought of John Henry Newman.

4 Leonard Sweet, VIRAL, How Social Networking Is Poised to Ignite Revival, published in the USA by Waterbrook Press, 2014, p 81.

5 Catechism of the Catholic Church, Veritas, 1994, Dublin, p 71.

6 Catechism of the Catholic Church, Veritas, 1994, Dublin, p 83.

7 5th January 1921, in a letter to a friend. The Heart of Matter, Harvest Book. Harcourt, Inc. A Helen and Kurt Wolff Book, San Diego, New York, London, p117-8.

8 From Christianisme et Évolution, 1945, p3, as quoted by N.M. Wildiers, An Introduction to Teilhard de Chardin, Collins Sons &Co. Ltd, London and Harper and Row, New York, 1968, p.133.

9 The Heart of Matter, A Harvest Book, Harcourt, Inc. A Helen and Kurt Wolff Book, San Diego, New York London. Copyright William Collins Sons & Co Ltd. 1978. Pp 15-16.

10 Col 1, 14-16.

11 In summarising Teilhard’s thinking I am indebted to Norman Wildiers’ An Introduction to Teilhard de Chardin, Collins Sons &Co. Ltd, London and Harper and Row, New York, 1968.

12 My Universe, in The Heart of Matter, p 201, A Harvest Book, Harcourt, Inc, San Diego, New York, London.

13 Catechism of the Catholic Church, Veritas, 1994, Dublin, p 87.

Leave a comment