The following talk was given in Haddington Road parish, Dublin, on 30 November 2023

This talk explains why we need the vision of Teilhard so badly, and outlines in broad strokes the nature of his inspiring vision.

LOVING CHRIST IN CREATION, WITH TEILHARD DE CHARDIN

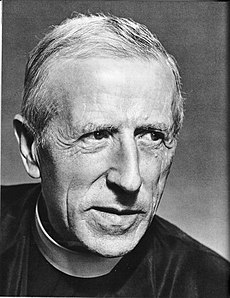

I have to begin by saying that no one is more surprised than myself that I am here giving a talk on the wonderful Pierre Teilhard de Chardin! I am not a theologian, or a scientist, or an academic, and I wish to speak from the perspective of an educated Christian-Catholic sitting in the pews, and specifically as a non-specialist. Simply someone who aspires to live the Christian life authentically in today’s world. So, what is it that brings me here this evening? It is my passionate conviction that Teilhard de Chardin has something of extraordinary value to offer to the Church and the world today, and that he deserves to be much better known than he is.

My own acquaintance with him began by accident, at a talk given to the French society in UCD way back in the late 1960’s by the then French ambassador. At that point in second year college, studying English and French, I was a convinced and enthusiastic Christian, (product of Loreto Convent school, Bray), much influenced by the wonderful autobiographies of St Therese and St Teresa. However, as a classical Christian, I found myself feeling a little out of place, a bit dated, as the world of modern English and French literature opened out before me. Hardly any modern author seemed to have any dimension of faith, and I was not identifying with them. I seemed to come from an older world, that had become passé.

However, one evening at the French society I providentially heard a talk by the French ambassador of the time about someone called Teilhard de Chardin. I was soon electrified! Here, finally, was a modern Christian! What a joy! What a relief! Here was someone who had drawn together the new evolutionary story of the universe and the Christian faith! Here was a wonderful, big, cosmic understanding of Christ that illumined all of reality as we now know it! Christ is walking ahead of us on the road of evolution, leading the way! All we have to do is to try and keep up with him.

I had gone into that talk with a seventeenth century spirituality. I left it with a spirituality for the twenty first century and beyond! And I was grateful. I went off, got hold of Teilhard’s books, and that vision of his became the happy foundation of my faith for the rest of my life. I no longer felt insecure about my faith in the face of the modern world, – someone intelligent had worked out the place of Christ in it, and this was no less than its Alpha and Omega, the very reason for it all! Indirectly thanks to the pandemic I have had the leisure to rediscover my passion for Teilhard after all these years, dormant under a busy teaching life. This led me to write a number of articles on him which were published in The Furrow, on the strength of which I was invited to come and give a talk about him this evening.

I tell this story because I think that the enthusiasm, hope and joy that Teilhard inspires in many of those who get to know him, the way he catches the imagination, is a significant factor in itself, and a sign of the Holy Spirit. He suddenly makes faith relevant in a totally new way for today’s world!

American theologian John Haught writes,

“Teilhard’s’ embrace of an unfinished and still-awakening universe is one of the main reasons why his writings mysteriously lift the hearts of his readers and make room for a new thrill of hope…that they had never experienced so palpably when reading and meditating on prescientific theological and spiritual works.“

THE TWO-STORY DILEMMA

It shows that Teilhard is fulfilling a real need, addressing a dilemma that thinking Christians in today’s culture often feel. Namely: how to bring together into one whole the two super-stories of reality offered by science on the one hand and the Christian faith on the other. Which of the two is “the greatest story ever told”?

For western civilisation it used to be the story of Christ, but that is now ceding first place to the new story of the evolution of life in the universe. The relationship of these two stories was, in fact, the drama of Teilhard’s own personal life: how to unify his own being both as a passionate scientist and a passionate Christian; how to live in a way that did justice to both aspects of himself. Teilhard can be seen as a great thinker, but in my opinion, he should be seen above all as a great lover, someone who was deeply in love with BOTH God and the world as God’s creation. How to love Christ in creation was the quest he set himself very early in life.

“Lord Jesus Christ, You truly contain within Your gentleness, within Your humanity, all the relentless immensity and grandeur of the world. And it is because of this, my heart, in love with cosmic reality, gives itself passionately to You. ” (Hymn of the Universe p 73)

ANCIENT VIEWS

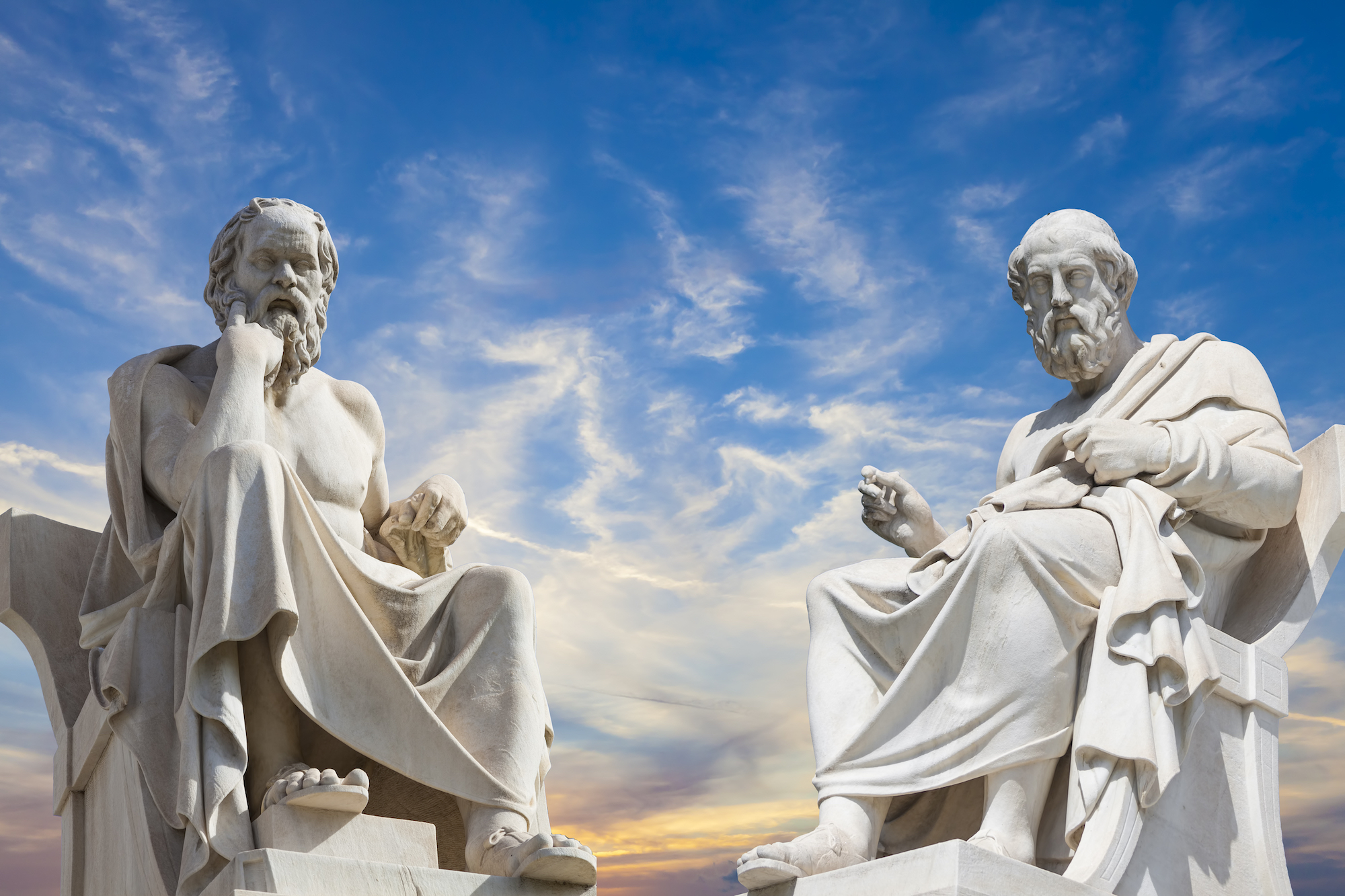

At this point I want to briefly set out, in the broadest of brush strokes, some of the issues that can challenge faith for today’s Christian. One is the matter-spirit dualism that has prevailed in the Church for the past twenty centuries. Dualism always saw a superior and inferior aspect in whatever it touched, – which was everything. You were to focus on the superior aspect (spiritual), and put up with the inferior (material) as best you could.

This idea came, not from a Hebrew source, not from the Bible, but from the Greek philosopher Plato, as early Christianity co-opted Greek philosophy in its efforts to make the new faith comprehensible to the Greco-Roman world. So, we had a higher spiritual nature and a lower bodily one, to be kept in check. This approach has coloured the spirituality of the Christian faith to an enormous extent, splitting reality into religious and secular domains of life. It led in many ways to suspicion of material reality as a place of temptation: “the world, the flesh and the devil” were waiting to get you.

Perhaps the best way to combat such temptations is to learn how to love the world as Christ loves the world, to learn how to love the flesh as Christ loves the flesh, who took on our human body. A much deeper incarnational spirituality is waiting to be developed, and Teilhard is a gateway to it.

The second thing is, of course, that thanks to science we have discovered a whole new picture of reality that simply didn’t exist before. Until the 17th century we thought the sun, moon and stars literally revolved around us here on earth! The Genesis account of creation was our history and science lesson, because we had no other source of information about our origins.

However, beginning with Copernicus and Galileo and the new scientific method, followed by the discovery of evolution by Darwin and Wallace, our knowledge about material reality has simply exploded. So we now know that we live in an evolving universe 13.7 billion years old, with billions of whirling galaxies, while under our feet matter descends to the quivering quantum level. We know that life has evolved very gradually over billions of years on this tiny planet, and that the cosmic story is a dynamic one, an evolutionary reality.

How on earth is the Christian faith going to make sense to modern generations who have this outlook on reality? What is the place of Christ in the cosmic story? In the evolutionary story? That is, does Christ have a place at all?

Teilhard worried about where this situation was leading: ‘Is the world not in the process of becoming more vast, more close to us, more dazzling…? Will it not burst our religion asunder? Eclipse our God?’ he writes.

Going forward, we need a much deeper concept of God.

“The God for whom our century is waiting must be:

-as vast and mysterious as the Cosmos

-as immediate and all-embracing as Life,

-connected to our effort as Humankind.

Any God who made the World less mysterious or smaller, or less important to us than our heart and our reason show it to be, that God, less beautiful than the God we await- will never more be the One to whom the earth kneels.“ (Heart of Matter, p212.)

HOW TO LIVE IN THIS WORLD?

For the Christian, is this world just a kind of transit-camp to eternity?

Or is it also a challenge, a task and a vocation? Does human activity – in home making, science, education, business, economics, politics, the arts… – have intrinsic value, and therefore religious worth?

Can we reconcile the Gospel teaching about detachment and self-denial, with the healthy love of earthly things and the effort needed to build a better world?

In The Future of Man Teilhard writes,

“From the time of the Renaissance…the cosmos has looked more and more like a cosmogenesis [world becoming itself]; and now we find that Man, in turn, is starting to be seen as an anthropogenesis [humanity becoming itself]. This is a major event which must lead us to radically modify the whole structure not just of our Thought but our Beliefs.”

Christianity used to be on the cusp of the wave of western civilisation. How was it being eclipsed by Modernity?

Teilhard saw the teaching Church as clinging to a static, outmoded cosmology and anthropology, rooted in ancient Greece. It had become too narrowly focused on salvation in terms of an after-life, and an individualistic piety, rather than on improving the world itself in its own right so as to build it as the Kingdom of God on earth. The Church was offering “too small a Christ” for today’s world. Instead the Church needed to look outwards to the fields white for harvest, and learn how to interpret Christ for today’s culture. This would give rise to a new holistic spirituality, energising Christians to go out and transform life on this suffering planet, through the values of Christ. In so doing, of course, our souls would be saved.

Teilhard laments,

‘There are times when one almost despairs of being able to disentangle Catholic dogmas from the geocentrism [everything revolving around Earth] in the framework of which they were born. And yet one thing in the Catholic creed is more certain than anything: that there is a Christ ‘in whom all things hold together.’ All secondary beliefs will have to give way, if necessary, to this fundamental article. Christ is all or he is nothing. ‘ (20th July, 1920.)

ANYONE LISTENING?

Those words were written over a hundred years ago, and sadly, for want of such a holistic, inspiring vision, Christ is becoming nothing for the increasing numbers of those who say they are ‘spiritual but not religious’ and who feel no need of him.

John Haught, writing in 2021, says, “Science’s great new discovery of a still emerging universe, however, is far from having become habitual to most Christian thinkers… Were Teilhard with us today, he would be saddened by the ongoing unresponsiveness of most Catholic thinkers to science… Given Christianity’s increasing irrelevance to the aspirations of countless scientifically educated people, the task seems more urgent than ever… Unfortunately, the relatively few Christian thinkers who have been rethinking their faith in a way that takes advantage of science are seldom taken seriously by the faithful at large, or by seminary instructors, or by religious officials.”

So this is the context in which Teilhard found himself, and the task he set himself was how to draw the faith story and the science story together. The difficulty being that each was absolute in its own way, and largely lived in their own separate worlds, – separate universes! He intuited that this was also the problem for every thinking Christian in tune with the modern world.

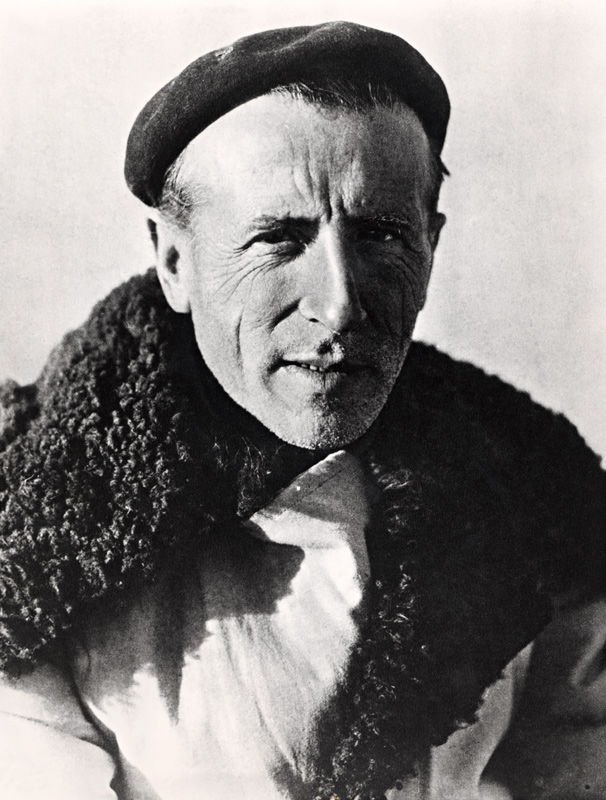

In addition to his theological and philosophical formation as a Jesuit priest, Teilhard was a Doctor in Palaeontology. His familiarity with the aeons of geological time led him to attempt a cosmic reinterpretation of the concept of original sin in the light of evolution. However, when these views were quietly reported to his Jesuit superiors in Rome, Teilhard discovered he had touched a nerve! He was silenced on the spot, forbidden to publish his views, nothing other than his scientific papers. He then spent the next twenty five years in China working as a geologist/palaeontologist, much appreciated by the Chinese, where he helped in the discovery of Peking Man. Meanwhile in the background of this scientific work he kept writing, and his works were only published by friends after his death in 1955.

KEY CONCEPTS

What key concepts enabled Teilhard to overcome the dualism that hobbled Christianity for so long in making its full contribution to the world?

First: the concept of UNIVERSAL EVOLUTION, in which everything emerges out of, and is related to everything else. Each thing exists as part of the whole, and the whole embraces the entire universe of space-time. It is all one.

Second: the concept of TIME AS A CONSTITUENT OF EVERYTHING. The evolutionary story is a dynamic reality that has not stopped. It is continuing in the human sphere right now, as our minds combine in ever more awesome ways.

Third: the discovery by Einstein that MATTER AND ENERGY ARE DIFFERENT FORMS OF THE SAME THING . E=MC 2 was an all-transforming insight![Energy equals matter multiplied by the speed of light squared.] To put it memorably, in Teilhard’s words, “Matter is energy moving slowly enough to be seen.” That is to say, there is a oneness in the basic structure of reality. Matter itself, the stuff of the world, is no longer inferior to the spirit but one with it. Spirit can be understood as a form of energy. ‘There is neither spirit nor matter in the world [as separate entities]; the stuff of the universe is spirit-matter.’

THE RISE OF CONSCIOUSNESS

Keeping those three things in mind, let me move next to Teilhard’s major work The Human Phenomenon, which he completed at the age of fifty-seven. Here Teilhard analysed the universe as a single whole, embracing these three insights and exploring their consequences.

It is an ambitious work in which he describes how matter developed ever greater complexity over aeons of time. This complexity of matter, from elementary particles upwards, brought about the rise of consciousness in all domains of life.

Evolution can be seen as the rise of consciousness throughout nature, and we can now say that we humans are the universe grown conscious of itself. Evolution is continuing, with a long way yet to go, and as humans, we are now responsible for it.

The future will bring us to converge more and more, a process in full swing today. “We gather here as one big tribe and Earth is the tent we all live in,” said Morgan Freeman as he opened the 2022 Men’s Football World Cup.

As the future comes to meet us faster than many of us would like, we need a strong hope for the future, and Teilhard uniquely provides it. He intuits that there will be an ultimate destiny for this convergence, a fulfilment, when everything in this world at last reaches a unity of hearts and minds, in many ways facilitated by technology. This authentic unity, however, can only happen through love, not coercion, uniformity or totalitarianism. He calls this moment of perfect unity the Omega point. As humans we are now responsible for our own future, and the future of our world. “The whole future of the Earth, as of religion, it seems to me, depends on awakening our faith in the future.”

Thus ends The Human Phenomenon. Teilhard presents this interpretation of the universe as an as an empirical analysis of reality, and independent of any faith story.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Now, what do you get when you apply this objective worldview to the Christian faith?

“Marvellous coincidence, indeed, of the data of faith with the processes of reason itself! What at first seemed a threat turns out instead to be a splendid confirmation!

Far from opposing Christian dogma, the vastly increased importance gained by humanity in nature results …in traditional Christology becoming relevant and vital in a wholly new way.”

Or, as John Haught put it more simply, “Evolution is the good luck of theology.”

Teilhard sees reality developing in four phases : cosmogenesis [world becoming itself], bringing about biogenesis [life becoming itself] bringing about anthropogenesis [humanity becoming itself] leading finally to Christogenesis [Christ becoming His Complete Self]. He claims Christ as the heart of this world.

EVOLUTION HAS A DIRECTION

As a true human being, Jesus the Christ is as much part of the universe as each of us. He is a homo sapiens, come to birth after millions of years of evolution. Christ, as the Human God, offers humanity a unique focus of unity as we incorporate ourselves into his Mystical Body, through the Eucharist that we eat and become. The Eucharist is the Risen Living Christ, whose flesh is now spiritualised matter. His resurrection is the proto-moment of the future destiny of creation and humanity, when it reaches the Omega point of perfect love. At that point earth and heaven will unite and become one.

This is a modern take on St Paul and St John, from whom Teilhard had always drawn his inspiration: “His purpose He set forth in Christ, as a plan for the fullness of time, to unite all things in Him, things in heaven and things on earth.” (Eph 1:9-10)

This is the destiny described in the Book of Revelation, written by St John:

“Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth…I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem coming down from God out of heaven, as beautiful as a bride all dressed for her husband…Here God lives among humans. He will make his home among them; they shall be his people and he will be their God; his name is God-with-them… The world of the past has gone. “Now I am making the whole of creation new.” (Rev 21, 1-5)

That the Christian faith fits perfectly with the evolutionary story of this universe is Teilhard’s considered view. The Church must claim Christ as the leader of cosmic evolution and the hope of humanity as a whole. Spiritual evolution on the part of humankind is what will prepare this final fulfilment. For Christians to take responsibility for this, at least in our own minds, would tap our best energies going forward. Imagine if this were to become the world’s newly-found faith, motivating all its best energies to make a better world!

THE IMAGE OF CHRIST NEEDED TODAY

The great Christ that the Church must offer to the world is the Christ for whom the cosmos was made. By the fact of his incarnation into matter, Jesus is related to the earth, its total past, present and future. Not only a Saviour of humans from our sinfulness, – though he is supremely that, the Divine Homo Sapiens is first and foremost the crowning glory, the supreme work of God in this cosmos. So, the Christ event should not be exclusively portrayed in the negative sense of salvation from sin, but also acclaimed in the positive sense of Christ leading this world towards its final fulfilment in a unified love. They are two sides of the same coin. In the words of St Paul:

For by him all things were created: things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible…; all things were created by him and for him. He is before all things, and in him all things hold together. (Col 1, 15-17)

EXPLORING CHURCH TEACHINGS MORE DEEPLY

Dutch theologian and general editor of the official French text of the works of Teilhard de Chardin, Norman M. Wildiers writes of him:

“His faithfulness to Church teachings is not to be doubted for a moment. His passionate love for Christ and the Church are beyond all question. The renewal he aimed at in theology never affected the kernel of Catholic teaching in matters of faith, but only its outer aspect, the way in which it was presented. He believed that the solution and renewal, so badly needed, were to be found, not in departing from traditional theology, but in exploring it more deeply.”

Teilhard deplored any spirituality that would set Christ against the world, as if we had to choose between being fully human and fully God’s. He thought the Church was too slow in developing the deeper, dynamic and cosmic understanding of Christ that the modern world needed.

“If we want to achieve the so much needed synthesis between faith in God and faith in the world, then the best thing for us to do is to dogmatically present, in the person of Christ, the cosmic aspect and cosmic role which make him organically the principle and controlling force, the very soul of evolution.”

Teilhard has been found by some to be over-optimistic, but he has no illusions about the difficulties involved. He writes in a letter to a young friend,

“Learn not to stifle the spirit of earth that is in us. But let there be no mistake. Those who wish to share in this spirit must die and be reborn, to themselves and to others…They must… change completely the basic way they value and act. In them, a new plane (individual, social and religious) must take the place of another one. This entails inner tortures and persecutions. The earth will only become conscious of itself through the crisis of conversion.”

CONCLUSION

Teilhard always maintained that his aim in writing was to set up a scaffold for a building that he hoped others after him in the future would construct. He wanted his work to open up of new ways of thinking for the Christian faith.

Forbidden to publish, he could not debate, correct and refine his ideas as he would have liked and needed. However, he found to his own satisfaction, the place of Christ in the cosmic story, the evolutionary story. It is one, single, great story and Christ is simply its Alpha and Omega, its beginning and glorious end.

In the view of Norman Wildiers “the real importance of Teilhard’s work lies in the tremendous power of inspiration which emanates from it.”

It was Teilhard ’s unified vision of the Whole that was the inspiration of the American Thomas Berry, considered to be the father of the ecological movement, which would make Teilhard indirectly its grandfather. Berry is quoted by the cosmologist Brian Swimme as telling him, “To see as Teilhard saw is a challenge, but increasingly his vision is becoming available to us. I fully expect that in the next millennium Teilhard will be generally regarded as the fourth major thinker of the western Christian tradition. These would be St Paul, Augustine, Thomas Aquinas and Teilhard.”

The ecological movement is primarily a movement of love for this world of ours, a love that, alas, has remained dormant until now in the Christian faith, until it is almost too late. Pope Francis has been trying to wake us up with his Laudato Si. Teilhard’s thinking, published just seven years before Vatican II, is thought to have influenced a number of its participants towards opening up the Church more to the modern world. In America today Teilhard’s thinking is being further developed by the Center for Christogenesis, and a two-hour TV documentary on him will be shortly released. [It was, in May 2024, and the link to it can be found under BIO in the list above.]

For me, what stands out in Teilhard is his whole, unified person as a magnificent human being, – priest, scientist, philosopher, mystic, friend and I would say, saint, a great lover of God and God’s extension in creation. One can even add in hero: if you had been a soldier on the front lines the First World War, wounded or dead, Teilhard would have come to carry you back to safety, as a stretcher bearer …. He survived sixty-four battles on the front lines, for which he was awarded the medal for bravery of the Légion d’Honneur, the highest honour of his country. His heart was as great as his mind, which passionately embraced the whole of reality where he sought out Christ in every fibre of the universe, that he might love Christ without limits. He uniquely teaches modern people to do the same.

‘Lord God, for my (very lowly) part I would wish to be the apostle -the evangelist- of Your Christ in the universe. For You gave me the gift of sensing, beneath the incoherence of the surface, its deep living unity.‘

(Hymn of the Universe)

Some time before his death at the age of seventy four, still denied any recognition by the Church he loved, he wrote, “O God, if in my life I have not been wrong, let me die on an Easter Sunday.” He died of a sudden heart attack on April 10th, 1955. It was Easter Sunday, day of the Risen Christ, to whom he had dedicated his life’s work.

It is my hope and prayer that one day he will be declared a saint and a Doctor of the Church. He is buried in New York where he spent his final years. May he rest in peace and rise in glory.

[For articles on Teilhard see @teilharddechardinforall.com ]